Table of Contents:

The Oxford Languages dictionary defines Religion as “the belief in and worship of a superhuman controlling power, especially a personal God or gods” or “a particular system of faith and worship”; the question of whether the term “Religion” can be applied to the beliefs of the Indo-Europeans and their ancestors, the Proto-Indo-Europeans (abbreviated as ‘PIE‘ or ‘PIEs‘ in the following), is a controversial one, to say the least.

Thus, before attempting to reconstruct Proto-Indo-European Religion, we need to take a look at the meaning of faith in our modern world and see if its definition applies to the beliefs of our ancestors or if a different one is needed to start with.

A Definition of Religion

Nowadays in the Western Hemisphere Christianity, Islam, and Judaism are the most influential faiths, both from a cultural and a historical perspective. These belief systems have in common that they’re centered around one god, one book, and a relatively small number of sects/churches in which its followers are organized. In the last decades, especially since the peace movements of the ’60s, complex eastern religious systems and philosophies such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism have gained not only recognition but an active following among Westerners. The issue that arose in this context, however, is that our concept of religion, dominated by the three aforementioned Abrahamic faiths was challenged by the decentralized, seemingly unorganized newcomers.

Let’s look at the Catholic Church in comparison with Hinduism as an example:

The Catholic Church is organized systematically, meaning there is a hierarchical top-down system, with the Pope at its head, through which information in regards to how to practice the Catholic faith is communicated to priests of all ranks and through them to the Catholic believers all around the world. Additionally, there is only one holy scripture, the bible, which gives answers to all of life’s questions, from the most trivial to the most fundamental. So even though there are multiple different Christian Churches that put emphasis on slightly different aspects of the faith, there is a very large degree of overlap due to the fact that they are all based on one book and the teachings and philosophies of Jesus Christ. These two elements give Christianity a very centralized and highly organized character on all levels of worship.

In Hinduism, on the contrary, there is no centralized body, organization, or system, which regulates the average Hindus belief. Neither is there a single text that one could refer to, a saviour or one all-mighty and all-knowing god. And thus it has been proposed by Westerners that Hinduism itself can’t be considered a religion at all, but rather many different but related belief systems that have interacted with and borrowed elements from each other over millennia. As a consequence, there is a considerable amount of overlap between them, which has contributed to the commonly held view of Hinduism as a singular religion, such as Christianity and Islam. But in actuality, there are many slightly different variations of Hindu religious practice and belief, spread all over South and Southeast Asia.

Reconstructing Proto-Indo-European Mythology

If we are to reconstruct Proto-Indo-European Religion, we are more likely to encounter a complex system of myths and legends, gods, and goddesses, with varying degrees of importance depending on location, time, necessity and the social standing of the worshipers, as is the case in Hinduism. Deities of fertility may have played a bigger role in areas where people relied on agriculture and pastoralism more heavily, whilst deities of justice and war were probably more important to the social elite. This means that some of these supernatural beings were probably only worshiped at certain times and places, whilst others were perhaps confined to certain parts of the populations, both in terms of social standings and in terms of locality.

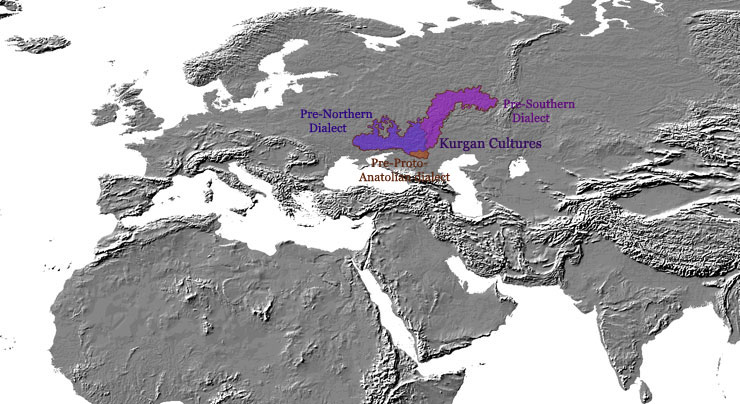

David Anthony (the author of “The Horse, the Wheel and Language”, see References at the bottom for more information) has pointed out one of these differences between Eastern and Western parts of the Yamnaya, an archaeological culture associated with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans and the dispersal of the Indo-European languages. The Western extremity of the Yamnaya Horizon was situated closely to the Venus-figurine worshiping Old Europeans (the native Europeans before the arrival of the PIEs from the steppe) and thus had incorporated some female deities into their own pantheon. This, however, did not happen within the Eastern group. On this basis, it can be assumed that the original PIE’s belief system was centred around male deities and that goddesses were a relatively “new” addition. However, in order to give a complete account of the pantheon that led to Western Indo-European mythology, the female deities will be included in the reconstruction below as well.

Summarizing the above, it can be concluded that (Proto-)Indo-European Religion did not exist as a single entity, but rather as a compendium of different mythical stories and tales, which were told and retold over a relatively large area, both in regards to space and to time. The same heterogeneity is true for the PIEs as an ethnic group; they should be regarded as many closely related, but not identical tribes and clans and not as an unified people in any sense, which further explains some of the differences between subsequent Indo-European mythologies.

Despite the differences, however, there were some elements, which seem to have been shared by most of the population over long periods of time and it is these elements, which shall be examined in the following.

Indo-European Belief Systems

In order for us to reconstruct PIE-beliefs, we have to take a look at the myths of their descendant peoples, as they themselves had no script with which they could have transmitted their stories and legends. There are four main areas of transmission which help us piece together a picture of Proto-Indo-European religious beliefs and practices:

- The transmitted pre-Christian belief systems of Eurasia, like the Norse, Roman and Greek Pantheons.

- Epic Tales like Homer’s poetry, including the Illiad and the Odyssey, the Scandinavian Sagas, collected in the Icelandic Eddas, or the Celtic myths of Ireland.

- Fairy Tales, such as the ones collected by the Brothers Grimm or Hans Christian Andersen, that have been transmitted orally for generations beforehand.

- Customs and Traditions, such as the erection of may poles in Germanic Countries.

By collecting as much information as possible from these areas of transmission and comparing them to each other, one can filter out the beliefs and stories all Indo-European peoples have in common and thus reconstruct PIE-mythology. Luckily this has been done before and we do not have to go through dozens of sources just to reconstruct a single deity or myth. The results of these comparisons will be presented below, starting with the Gods and Goddesses.

The Proto-Indo-European Pantheon

As should have been made sufficiently clear by now, the Proto-Indo-Europeans were polytheistic, meaning that they worshiped many gods, rather than one. We can say with some certainty, that among them was a Dawn-Goddess, a Mother-Earth-Goddess, a God of Thunder, a God of Water, a Sun-God, the so-called Divine Twins, and possibly a God of Craftsmanship. They were led by a Sky Father, whose children included at least the Dawn-Goddess and possibly the God of Thunder and the Divine Twins. They were strongly associated with horses, such as the Anglo-Saxon Hengist and Horsa, the twin brothers who first settled England and whose names literally mean ‘stallion’ and ‘horse’, respectively. The Sun-God is described as a Seer who drives across the sky in a chariot, pulled by various animals in different traditions. The swastika may have been a symbol associated with him (or her).

The chieftain of the Gods and Goddesses, the Sky Father, was often described as ‘all-knowing’ and ‘all-seeing’. His daughter, the Goddess of Dawn is assumed to have been the most beautiful among the PIE-Pantheon and may have been called upon for poetic inspiration. It is uncertain though possibly that her mother was the Earth-Goddess and that she was the Sky Fathers spouse. She may have been inspired by the female deities of the Old Europeans. If she was in fact the spouse of the Sky Father, it seems likely that she was the mother of the God of Thunder and the Divine Twins as well. In many Indo-European traditions the former is associated with the slaying of the forces of evil, such as the Norse Thor or the Greek Zeus.

Apart from these main members of Proto-Indo-European mythology, we also have some creatures of lesser (or at least different) significance, most notably the Fates, who are most often represented as three women which spin the destinies of both gods and mortals and are most famously known as the Greek Moira or the Scandinavian Nornes.

Gods Throughout Time

The ancient deities of the PIEs developed differently in the various Indo-European societies and could swap roles over time. A good example of this is the Germanic Tyr (Old Norse Tyr, Old English Tiu, Old High German Ziu), whose name can etymologically be traced to the Sky Father, but who was degraded to the God of War and Justice in North Germanic mythology and replaced by Odin, the Allfather. It is unknown what the exact reason for this development was; perhaps Wodan/Odin was the name of a deity indigenous to pre-Indo-European Northern Europe, who could not be replaced by the Sky Father but who took on some of his characteristics over time.

Another example of gods changing functions are the Roman Jupiter and the Greek Zeus, both etymologically descendant of the Sky Father. Both gods are well known for their association with thunder, an attribute they’ve clearly taken over from the God of Thunder, who seems to have disappeared from these pantheons as a distinct deity as a consequence. The fact that the God of Thunder is the son of the chieftain of the gods may explain this fusion to a certain degree; as there already was a kinship relation combining father and son into one god seems plausible.

Myths and Legends

A fair number of myths, stories and fairytales across Eurasia appear to have come down to us from our Proto-Indo-European ancestors.

For example, there seems to have been a shared Creation Story, which shall be summarized here in a few sentences to give a taste of PIE storytelling:

In the beginning, there was nothing. Then, a primordial being (or possibly twins) emerged from two opposing forces in the emptiness of space. The being feeds on an animal, possibly a cow, and is slain by the Gods, who form the world from its parts.

This particular stories has been interpreted as ‘the first sacrifice’ after which Indo-European ritual sacrifices in general are presumably modelled.

In a few societies, a legend of a war between the Indo-European gods and a different set of deities is mentioned, such as the Aesir and Vanir in Norse mythology, or the Olympians and the Titans in Greek legend. This has been interpreted as the clash between the IE newcomers and the indigenous populations by some scholars and as the subjugation of the lowest class in Proto-Indo-European society, the agriculturalists, by others. The latter interpretation makes sense in the case of the fight between the Sky Gods and Fertility deities in Norse mythology, but not so much in the case of Greek or Vedic myth.

The dragon or serpent slaying legend seems to have been a very popular tale among our prehistoric ancestors as well, given that the motive appears not only in pagan but in medieval Christian legends as well, such as the German Song of the Nibelungs (the Scandinavian Volsung Saga) or the dragon-killing Saint George. Matasovic reconstructed “*gwhent h3egwhim ‘he slew the serpent‘” on the basis of different expressions across Indo-European cultures. The original killer of the serpent probably was the God of Thunder, as has been mentioned earlier.

There also was talk of a world tree, such as the Germanic Yggdrasil, which connects the different spheres or plains of existence, the Earth (Underworld), the “middle-earth” (The world of the humans) and the Sky (the world of the gods). Whether this myth was a original invention of the PIEs or a foreign influence, possible from North Eurasian shamanistic practices, remains controversial.

Religious Practice

In all versions of the aforementioned story of the beginning of the universe, either the universe itself, the gods, life, or humanity springs forth from a sacrifice, which points to the importance of this practice in PIE society. These sacrifices were conducted in the form of a ritual by a King-Priest, who was the spiritual and worldly leader of a Proto-Indo-European clan or tribe. It has been speculated that horse sacrifices in which the animal was dismembered were a recreation of the original sacrifice made by the gods to create the universe out of the different body parts of a primordial being.

Apart from horses, the early PIEs also sacrificed cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs, with the former probably being more important or more “valued”, both by men and gods, than the latter. But there also is the possibility of a more gruesome practice. Whilst not being attested for PIE-society per se, there is evidence for human sacrifice in some descendant Indo-European societies. The ancient Germanic tribes, for example, strangled and then drowned people in swamps whilst the Celts ritually burned them for the god Taranis. These specific religious methods of murder may have been part of something known as ‘the threefold death’, each method representing one of the three parts of PIE society: Hanging represented the Priest Caste, burning the Caste of the Warriors and drowning the Caste of the Farmers and Herders. According to Mallory & Adams Odin hanging himself is another representation of the sacrifice of the first function.

The priests conducting these rituals probably had a very distinct social standing and possibly even abided by a distinctive code or creed and enjoyed certain privileges, as Matasovic points out by comparing Vedic to Roman priests:

Matasovic also provides a prayer, that has been found in the Italic and Indo-Aryan branches of the Indo-European family tree, and thus could have been in use by some parts of the PIE-population: “A particular formula associated with IE prayers is ‘protect men and livestock‘, PIE *wiHro- *pek’u- peh2-, reflected as Umbrian ueiro pequo … salua seritu, Lat. pastores pecuaque salua seruassis, Av. θrāyrāi pasvā vīrayā, Skr. trāyántām… púru am páśum.” (Matasovic 2018, p. 16). He also mentions magic in this context, and one particular ‘spell’, although not reconstructed in its Proto-Indo-European form, is found all across the IE horizon, with the most famous version perhaps being the Merseburg Incantations, the only direct attestation of Continental Germanic Paganism:

Phol ende uuodan uuorun zi holza.

du uuart demo balderes uolon sin uuoz birenkit.

thu biguol en sinthgunt, sunna era suister;

thu biguol en friia, uolla era suister;

thu biguol en uuodan, so he uuola conda:

sose benrenki, sose bluotrenki, sose lidirenki:

ben zi bena, bluot si bluoda,

lid zi geliden, sose gelimida sin![14]Phol and Wodan were riding to the woods,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merseburg_charms (10/07/2020)

and the foot of Balder’s foal was sprained

So Sinthgunt, Sunna’s sister, conjured it;

and Frija, Volla’s sister, conjured it;

and Wodan conjured it, as well he could:

Like bone-sprain, so blood-sprain,

so joint-sprain:

Bone to bone, blood to blood,

joints to joints, so may they be glued.[15]

The Afterlife

Lastly, we will look at the end. Quite literally, in this case.

There are differing accounts regarding the journey into the next world in Indo-European societies, so there are only a few elements that can be reconstructed for PIE-mythology with at least some degree of certainty. A fairly widespread feature seems to have been the journey across a river, which waters can cause either forgetting or wisdom (or possibly both, as one doesn’t necessarily exclude the other). The underworld may have been guarded by some sort of canine, such as the Cerberus in Greek mythology, although Matasovic argues that this particular element may have been borrowed from a non-Indo-European source.

Whether reincarnation instead of an afterlife in some sort of otherworld was a widespread belief remains controversial, but there is some evidence among Indic and Germanic myths to support this assumption. Not only the lives of individual men (and gods) could have been seen as cyclic, but the universe as a whole, as is evident in the rebirth of the world after the Norse apocalyptic myth of Ragnarok.

Although there is much that can be reconstructed from Indo-European mythology, there is much more which we will never be able to recover. So this overview is, at best, a rough outline of the rich myths and legends, which were once told around the campfires of the Eurasian steppes.

References:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Indo-European_mythology (07/07/2020)

- Anthony, David W.: The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World, Princeton University Press 2007.

- Matasovic, Ranko: A Reader in Comparative Indo-European Religion. Zagreb 2018.

- Mallory & Adams: The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford 2006.

- Puhvel, Jaan:Comparative Mythology. Baltimore 1989.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merseburg_charms (10/07/2020)

Subscribe for regular Updates:

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Spreading high quality knowledge about the ancient past can help us understand the world we live in today and find our place within it. Your donation helps European Origins to conduct more extensive research and thus provide more information about our ancestors for free for everybody who is looking for it.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

The Cord Ware people in the northern half of Europe, surged Eastward, combining with the Andronovo culture in the Russian Steeps, forming the Shantastra Culture. This culture surged all the way downward across Asia. It is my own contention that their organized religious belief system forms the basis for all of earth’s religious beliefs today. I believe at least a version of the messianic belief system originated among these people, for example. No doubt, this continually surging wave of immigrating humanity was maybe the largest in human history, and most certainly the most profound and long lasting, affecting us in huge, often violent, dramatic ways, even down into our own day.

LikeLike

Pingback: The History of the Indo-European Language Family | European Origins

Reblogged this on Muunyayo .

LikeLike

Pingback: Proto-Indo-European Religion: Gods, Myths and Practices — European Origins | Die Goldene Landschaft

Reblogged this on Rekkared.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Pingback: The Proto-Indo-European Myth Of Creation – European Origins

Pingback: Proto-Indo-European Society: A short Introduction – European Origins

Pingback: The Indo-European Migrations – How We’re All Connected – European Origins

My pleasure. This kind of information is invaluable, I wish it were more widespread. So I’m glad to know other folks take an erudite interest.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much, it means a lot! Feedback like yours inspires me to keep on working.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I admire your research and restraint. Your work is admirable in a field that deserves more attention and sometimes doesn’t deserve the kind of attention it does get.

I know for myself, my own personal readings into European comparative religion and myth has proven incredibly satisfactory.

Cheers, at any rate!

LikeLiked by 2 people

As far as I know these believes and practices may have been inspired by Marija Gimbutas Old Europeans and not by the Proto-Indo-Europeans.

LikeLiked by 3 people

In pre-christian Central-Europe under the socalled Germanics (a Roman invention which did never exist) women had a leading role as priests, spiritual advisers and prophets. The idea of a godfather came with the patriarchal Christian belief which eliminated all these egalitarian ambitions of our ancestors. Besides, the oldest spiritual or religious sculptures found here in Germany like the Venus of Willendord (30,000 BC) are only female. Cheers.

LikeLiked by 3 people